March 31st, 2020

March 31st, 2020

4:41 min read

4:41 min read  1289 words

1289 words

I recently wrote about the privatisation of university buildings1 and how that’s a Bad Thing™.

Between the time I enrolled and graduated at Camberwell College of Arts, the building went from being largely open to the public to a situation where access to the building, and movement inside it is tightly controlled by access cards, remote-controlled gates, cameras, visitors lists, fencing, and private security guards. The Royal College was already in a similar state when I got there (plus the private landlord adding their own power mechanisms to the pile in the form of inspections, hostile architecture, and more security guards).

The move to online teaching over the last few days is a dramatic escalation of this same movement. While our department heads are doing their best to get everyone onto Zoom calls or Hangouts as soon as possible, let’s remember what these apps are: entirely private, venture-funded1, data-collecting, exclusive to anyone without high-end internet, for-profit spaces designed to reproduce the hierarchies of business meetings. Access is finely graded and revokable at any time if you stop paying your subscription fees or otherwise become a nuiscance to the institution.

Zoom, which has somehow become the default choice for online teaching, embodies all of these attributes. It’s a particularly good example of how institutional power structures are hard-coded into these apps, beginning with who gets to control the knowledge about what’s happening on the platform1:

Zoom allows administrators to see detailed views on how, when, and where users are using Zoom, with detailed dashboards in real-time of user activity. Zoom also provides a ranking system of users based on total number of meeting minutes. If a user records any calls via Zoom, administrators can access the contents of that recorded call, including video, audio, transcript, and chat files, as well as access to sharing, analytics, and cloud management privileges.

Nothing escapes the administrative gaze. Further, it can look beyond what happens in any given Zoom meeting and reach into whatever physical space we happen to be calling in from:

For any meeting that has occurred or is in-process, Zoom allows administrators to see the operating system, IP address, location data, and device information of each participant. This device information includes the type of machine, specs on the make/model of your peripheral audiovisual devices like cameras or speakers, and names for those devices (for example, the user-configurable names given to AirPods). Administrators also have the ability to join any call at any time on their organization’s instance of Zoom, without in-the-moment consent or warning for the attendees of the call.

With shared workspaces shuttered and everyone forced to connect from home, this data now illuminates formerly intimate spaces: my IP address no longer bounces between coffee shops, university, and the library, but invariably points to my house, and my device information now describes hardware I keep in my bedroom.

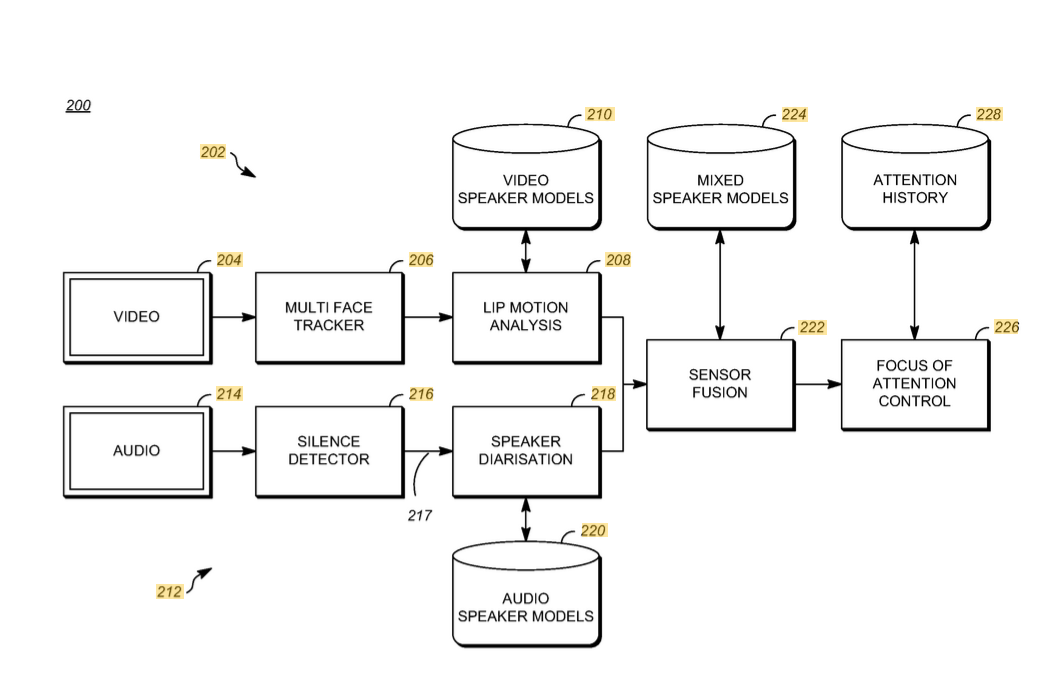

But the most dystopian Zoom feature of all has to be Attendee attention tracking. In a 2018 article1 the company describes the feature and its potential use in an educational context as follows:

Cool feature alert! Attendee Attention Tracking in Zoom can help you monitor your students’ attention to your shared presentation. Whether it’s a video, a powerpoint, or your desktop, if Zoom is not the app in focus on a student’s computer you will see a clock indicator next to their name in the Participant box […] It may also be helpful to let your students know that you will be grading this metric. In the virtual classroom, anything you can do as educators to facilitate engagement and attention will translate to continued success in the classroom.

Again, this information only flows up toward the administration (and in semi-anonymised form to Zoom and its advertising partners1). Attendees (remember when we were students) are seen, but can’t themselves see beyond whatever material the organisation has made available.

Management at the Royal College have announced they will be rolling out Zoom to all students, but it is unclear which of its administrative features they’re planning to use, what information they’re storing, and for what purpose. But even if they didn’t use any and stored nothing, the fact that these control mechanisms are built into the platform to be turned on at any moment without any real option to dissent, is damaging enough. You can’t practice institutional critique when the institution is sitting on a giant mute button1.

Not that this kind of privatised software-space is new to education. Other ed-tech junk like Edublogs, Moodle, Panopto (nice), Connect2, G-Suite, and “The Intranet” fit largely similar descriptions. But under social distancing, these apps have become impossible to avoid.

This is why it is now more necessary than ever to interrogate these virtual spaces as we would the classroom and, as Hal Foster puts it, “find fissures within this world, to pressure these cracks, and open up a little running room”1.

Some of this has already started: public Whatsapp groups provide an unofficial commentary track to most official Zoom meetings. Multiple programs at the RCA have taken over their formerly marketing-oriented Instagram accounts and are using them to critique the institution. Official emails are screenshotted and discussed in cross-institutional Slack channels. This isn’t to say that these platforms don’t have their own problems, but by creating our own spaces within them, we’re at least avoiding the most immediate level of administrative control. The next step is to think about how we want this online-learning thing to work, and building our own systems (not necessarily technological) to support that.